The US War For The Sahara

Proxy Wars Heat Up In The Sahara Desert

Who will win control?

Pursuing Terrorists in the Great DesertThe U.S. Military's $500 Million Gamble to Prevent the Next Afghanistan

by Raffi Khatchadourian January 24th, 2006 11:28 AM

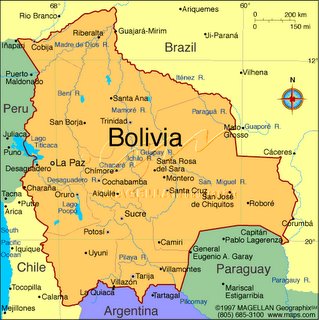

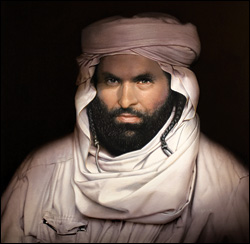

In the early months of 2004, a lone convoy of Toyota pickup trucks and SUVs raced eastward across the southern extremities of the Sahara. The convoy, led by a wanted Islamic militant named Ammari Saifi, had just slipped from Mali into northern Niger, where the desert rolls out into an immense, flat pan of gravelly sand. Saifi, who has been called the "bin Laden of the Sahara," was traveling with about 50 jihadists, some from Algeria, the rest from nearby African countries such as Mauritania and Nigeria. There are virtually no roads in this part of the desert, but the convoy moved rapidly. For nearly half a year Saifi and his men had been the object of an international hunt coordinated by the United States military and conducted primarily by the countries that share the desert. Soldiers from Niger, assisted by American and Algerian special forces, had fought with Saifi twice in the past several weeks. Each time, the convoy escaped. Now it was heading further east, toward a remote mountain range in northern Chad. At the time, Saifi was by far the most sophisticated and resourceful Islamic militant in North Africa and the Sahel, an expansive swath of territory that runs along the Sahara's southern fringe. In the Sahel, the Sahara's windswept dunes gradually reduce to semi-desert, and then, further south, become arid savanna. The terrain extends roughly 3,000 miles across Africa—from Senegal through Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Chad, and into Sudan. It is awesome in its scale, poverty, and lack of governance. Troubled by restive minorities, environmental degradation, economic collapse, coups, famine, genocide, and geographic isolation, the Sahel has been described by one top U.S. military commander as "a belt of instability." (Last year, the U.N. ranked Niger as having the world's worst living conditions; Mali and Chad were among the five worst.) The region is also home to some 70 million Muslims, and since 9-11 there have been reports that Islamic radicals from other parts of Africa, as well as from the Middle East and South Asia, are proselytizing there, or seeking refuge from their home countries, or simply attempting to wage jihad. Read more at the link above.